There are a few things in a professional context that really get under my skin. One of the main things that really upsets me is the thought of patients not being properly looked after and thoroughly investigated when needed.

The idea for this blog came after I saw a 50-year-old male endurance athlete 6-weeks ago who I suspected had a sacral bone stress injury (BSI). He required MRI imaging, not only to confirm the diagnosis but also to take a wider look at his bone health should there have been a BSI found. Despite providing this patient with a referral letter his health insurer refused to fund any further investigations on the basis that MRI imaging would ‘not change his management/treatment’.

This didn’t sit well with my conscience and I felt that as stakeholders in his care, that his health insurance company was failing to act in his best interest and act with due diligence. As I reflected on the situation, I thought that this would be a good case to examine my own ‘clinical reasoning’ and explore what the evidence and expert opinion would advise in this situation.

The patient

A 52-year-old male former Ironman triathlete, Mr X, who in the previous 4 months had switched his focus to improving his marathon time. This meant he was no longer swimming, cycling AND running but ONLY running six days a week. He also started to incorporate intense running workouts such as track intervals, tempo runs and hill workouts which he had not done regularly in the past. He was doing some simple core exercises but not a more holistic/comprehensive strength and conditioning program.

His weekly mileage had progressed from 30-35km/week at the start of the year to just over 100km in the 3 weeks before I saw him (an increase of more than two thirds).

He had been experimenting with different footwear, looking for a performance advantage opting to complete his interval and tempo workouts in a light weight carbon plate running shoe.

His problem (aka presenting complaint)

Mr X came to see me concerned about a two-week history of sudden onset left lower back and high buttock pain which initially developed on a Sunday long-run after a hill session the previous day. He had been able to complete his run but had struggled and was aware that he was altering his gait in the last 4 miles – limping slightly.

Later that day he had some low level (2/10 pain) and awareness of an ache when lying in bed. He was sufficiently concerned by his symptoms that he swopped his Monday easy-run for a turbo trainer session which was pain-free. A day later, on Tuesday, he tried to run after but had to stop due to a rapid increase in pain after around half a kilometer.

He took a whole week of rest from running after this and after two or three days reported that he’d been able to walk around and do all his usual day to day activities without pain. Unfortunately, when he tried to run again, his pain quickly returned within half a kilometer (although slightly less severe than the previous attempt) and that’s when he looked for help and got a referral to see me from his health insurer.

Past medical history

When assessing any individual it is important to consider their health holistically, as other medical conditions may impact on or may even be a cause of the problem that they’re attending physiotherapy for.

In Mr X’s case, from a musculoskeletal perspective, he had a history of a traumatic fracture of his right scaphoid (a small ‘carpal’ bone in the hand) fracture from a cycling accident around 10 years ago. He however, was not aware of any underlying systemic health problems (e.g. heart/rheumatological) or history of serious illness in the past (e.g. cancer) and he took no regular medication.

Lifestyle factors

Diet: Mr X reported to eat a balanced diet but was careful to avoid processed foods and foods high in fat as he wanted to ‘keep lean’. Which he felt was important for endurance athletes.

Sleep: Averaged 7.5 – 8 hours per night

Body Mass Index: 18, with a slight loss of weight reported over the past 3-4 months.

Non-smoker / low alcohol consumption

Reflective commentary

Before getting onto the point of carrying out a physical examination of Mr X it was important to consider the likely underlying diagnoses for his symptoms and how best to clinically test for each one.

Based on anatomical location the three key differential diagnoses in my mind were:

1. Lumbar spine (low back) pathology (e.g. lumbar facet joint/disc)

2. Sacral ala bone stress injury

3. Hip bone stress injury (e.g. femoral neck)

I felt that lumbar spine involvement was less likely as he had not reported any pain or restriction on movement of the lumbar spine and there were no neurological features such as pins and needles and numbness.

I was much more suspicious of a bone stress injury as Mr X had a number of ‘risk factors’ associated with bone stress injuries, including:

- A history of a marked increase in training load leading up to the onset of symptoms (30km/week to 100/km> & the introduction of intense interval/tempo sessions).

- The fact that his symptoms were provoked by weight bearing and specifically impact activity.

His symptoms worsened rapidly with running rather than getting better as he ‘warmed up’ when running. - The presence of night pain for 2 to 3 evenings after the initial onset of symptoms and resolution of pain after removing impact activity (running) after the first week of onset.

- He also had a low BMI and reported around 1kg of weight loss over the past 3-4 months, which suggested that his calorific intake was not meeting his demands and as such he may be at risk of a relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S which we’ll discuss more later).

The location of his symptoms in the left lower back and high buttock region raised the possibility of a left sided sacral ala fracture (especially as he had no reported problems with lumbar spine movement). This was also a pattern of symptoms that I recognized from other athletes who have gone on to be diagnosed with sacral stress fractures and something that I have experienced personally and written about previously (‘What I learned from my sacral stress fracture’).

Summary of physical exam/clinical assessment:

- Observing Mr X walk into the clinic he had no obvious limp and a normal flowing walking pattern.

- In standing he had no pain whilst stationary and movement of his lumbar spine/lower back range of movement was full and pain-free in all directions.

- He was able to squat, lunge and duck walk without pain.

- Single leg hopping 8-10 times on the symptomatic left side reproduced his pain (rated at 3-4/10 on a pain scale).

- Examination of hip movement and muscle strength was normal and did not reproduce his pain (including fulcrum and FADIR tests)

- Mild discomfort in the left sacral region was reproduced on FABERs test (see picture below) and with direct palpation of the left sacrum.

- There was no focal tenderness on palpation of the lumbar spine/lower back and neural sensitivity/dynamic tests were all normal.

Clinical diagnosis (i.e. a non-image based diagnosis)

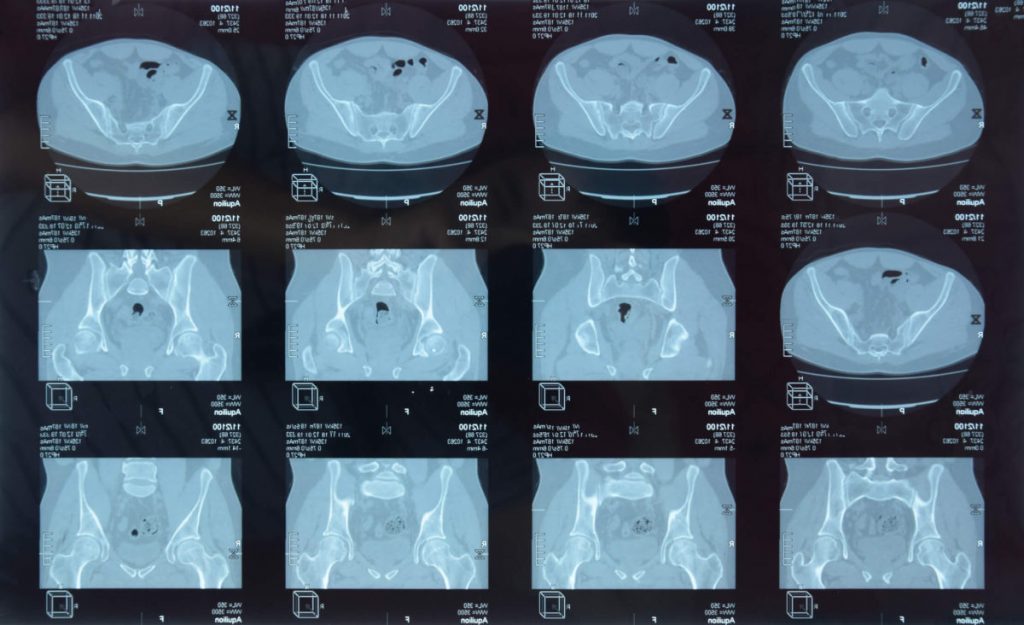

The balance of clinical findings appeared to have excluded the lumbar spine and hip as the most likely sources of Mr X’s symptoms, which were reproduced on direct left sacral palpation, maneuvers causing shearing force through the sacrum (FABERs test) and on high impact (hopping).

My initial advice to Mr X was to assume that his symptoms were due to a sacral bone stress injury until proven otherwise by appropriate MRI imaging.

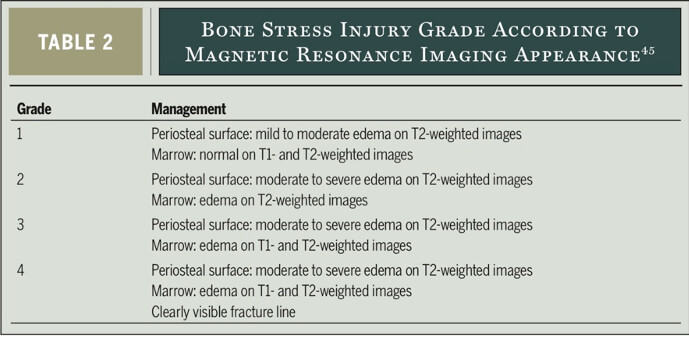

I made him aware that bone stress injuries can occur on a spectrum commonly graded from 1 (least severe) to 4 (most severe, full fractures). This was so that he understood the importance of not continuing to do any activity or exercise that caused any discomfort whatsoever as this might lead to the progression to a higher-grade BSI that requires more time to heal.

The table below taken from Stuart Warden and colleagues excellent paper ‘Management and Prevention of Bone Stress Injuries in Long-Distance Runners’in 2014 shows how bone stress injuries can been graded based on MRI imaging.

I also discussed a prompt referral to a trusted Sport and Exercise Medicine Colleague, Dr Catherine Spencer Smith, so that appropriate MRI imaging could be completed to gain a definitive diagnosis and also allow for other metabolic factors that may contribute to a BSI if one was found.

Mr X understood the initial treatment plan but unfortunately, as we already know, his health insurers did not sanction a referral for further investigations on the basis that it would not change his treatment.

So let’s consider how imaging in this case (or similar cases) may impact on the care of individuals with suspected bone stress injuries.

It is important to acknowledge that any diagnostic imaging or test must be done with clear consideration of how the result is likely to direct the care that an individual receives. It is well documented, for example, that MRI imaging for ‘simple mechanical back pain’ in systemically well individuals is not required, as the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) state: ‘Requests for imaging by non-specialist clinicians, where there is no suspicion of serious underlying pathology, can cause unnecessary distress and lead to further referrals for findings that are not clinically relevant’.

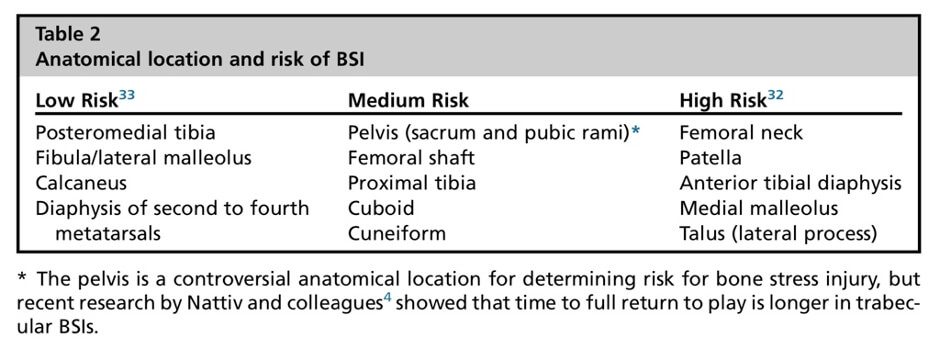

- In Mr X’s case the decision of his health insurer that MRI imaging was not necessary is a valid one if we are only concerned with managing the ‘presumed’ sacral BSI and not providing the patient with the best prognostic timeline possible. Afterall a sacral BSI is not considered to be a ‘high risk’ anatomic location in terms of their ability to heal with appropriate rest, as the table below shows, taken from Tenforde and colleagues paper ‘Bone Stress Injuries in Runners’.

Looking at the bigger picture: Treating the individual, not just the injury

If we are concerned however with the holistic well-being of individuals with possible bone stress injuries, then failure to obtain a definitive diagnosis is a missed opportunity to examine if there are any wider/systemic health problems of which a bone stress injury is a symptom. This might include intrinsic risk factors such as low Vitamin D, low bone mineral density (BMD), and hormonal imbalances that have an impact on bone health.

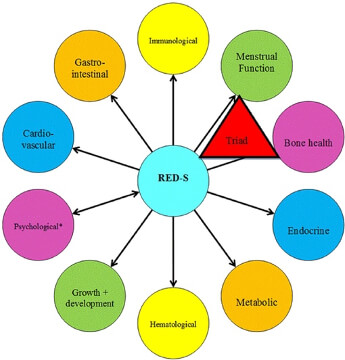

In Mr X’s case his recent weight loss, low BMI and likely sacral BSI could be considered to be possible symptoms of Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (aka RED-S), that is essentially a chronic failure to consume adequate calories to meet energy expenditure.

An excellent paper from the International Olympic Committee ‘Beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport’ highlights the complex and broad ranging health related consequences of RED-S. Ranging from impairment of metabolic rate, menstrual function (not for Mr X!), bone health, immune function, protein synthesis and cardiovascular health. Their nice schematic below highlights that bone health is just ONE of many areas that can be impacted by RED-S, and underlines the potential danger of failing to investigate Mr X as his symptoms may be underpinned by much wider ranging systemic health problems.

I have personally identified a patient who I suspected had a sacral stress fracture which was confirmed on MRI after referral to a sports medicine doctor. Subsequent follow-up investigations included a DEXA scan (to assess BMD) and blood tests relevant to bone health which revealed reduced BMD in the lumbar spine (osteopenia), Vitamin D deficiency, reduced testosterone levels and a pituitary adenoma. All of which have been appropriately medically treated and have allowed the patient to return back to running and exercise in a sustainable injury-free manner. Had this patient been offered the management of Mr X his outcome is likely to have been very different with on-going risk of bone stress injury and wider medical complications.

So, what happened to Mr X?

Mr X thankfully decided to self-fund his referral to see Dr Spencer-Smith and was subsequently found to have a grade one left sacral ala stress fracture. A follow-up Dexa scan revealed mild osteopenia in the lumbar spine but normal values elsewhere. He had slightly low Vitamin D and he was found to have a slightly overactive thyroid which are now being treated. He has also been referred to a dietician to address his nutrition and to help him ensure that he can adequately fuel for his energy demands and avoid RED-S.

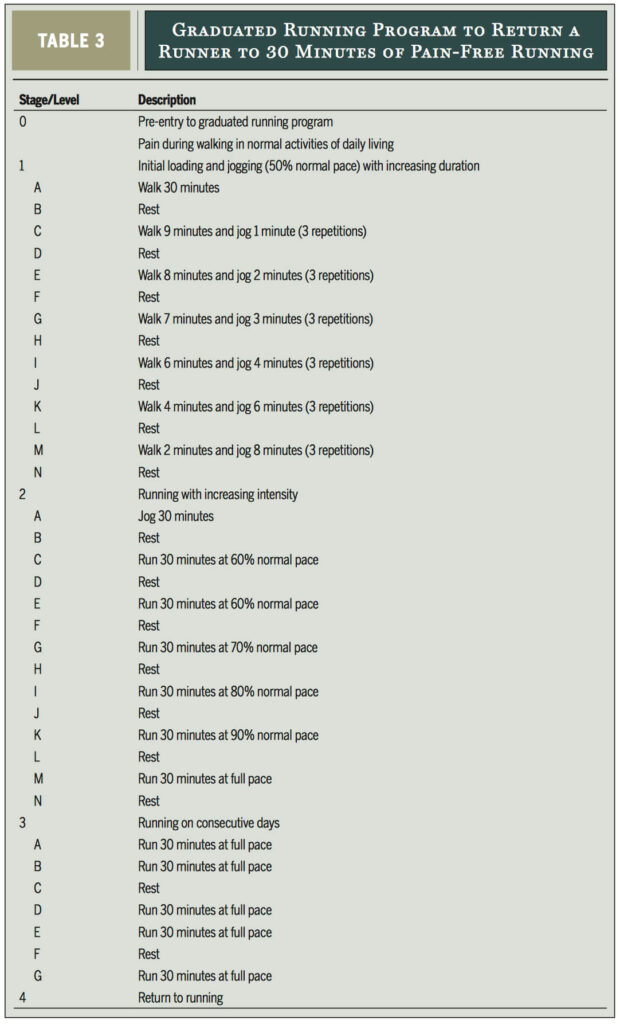

From a musculoskeletal perspective he is now around 4 weeks into his rehab program which has focused on non-impact cardiovascular maintenance via a turbo trainer, non-impact core, and lower limb strengthening exercises all with strict attention to form and ensuring that they are completely free of pain.

Over the next 4-6 weeks, Mr X will be guided through a reintroduction of impact exercise and a graduated return to running program ensuring that he remains symptom free. He will follow a program with similar principles as the one outlined by Warden and colleagues below.

A rapid increase in Mr X’s training load as he turned his focus to running was likely to be the most significant ‘external risk factor’ in the development of his injury. As such he has received advice around the importance of building a sustainable training program taking into account principles such as ‘Acute to Chronic Workload Monitoring’ (see my previous blog regarding this concept here). I have found using a UKA accredited running coach to be incredibly useful personally, as well as for my patients, in developing an appropriately periodized and graduated training program, helping to avoid rapid peaks and troughs in training that can be problematic.

Mr X is considering the potential benefits of including some non-impact cardiovascular training into his running focused long-term training program to mitigate the repetitive mechanical loading associated with running. He is also more understanding of the potential benefits of allocating time in his weekly schedule to complete at least one strength and conditioning session (in addition to his existing body-weight core routine) to ensure that he has both good strength and impact absorbing qualities in his running relevant muscle groups as well improving his neuromuscular coordination.

Wrapping things up

Having considered my initial thoughts on the best management of Mr X, I enjoyed the challenge of reflecting on my thought processes (clinical reasoning) as to the optimal way of managing his symptoms.

I feel strongly that where there is a clear clinical suspicion for BSI that definitive imaging should be obtained and all individuals with bone stress injury should have their BMD and bloods checked to screen for underlying risk factors. This approach is largely supported by the literature (although not unanimously) as Warden and colleagues note:

‘Ultimately, runners who display clinical signs and symptoms of a possible BSI require imaging to confirm suspicions and to make a definitive diagnosis… Of the imaging modalities currently available, magnetic resonance imaging is the modality of choice because of its superior contrast resolution, lack of exposure to ionizing radiation, and combined high sensitivity and specificity’.

If you have any injury concerns seek expert help to make sure that it is properly checked out. I’m here at [email protected] if you need your injury sorted.

Keep safe & happy running.

Scott